James Nichols

It was Friday, April 21, 1995. I was working in the newsroom of the Detroit News on Lafayette Blvd. when I got word that the feds were raiding a farmhouse in Decker, a rural community about two hours north of Detroit. It was linked to the Oklahoma City bombing just two days before that claimed the lives of 168 people and injured more than 600 others.

I jumped in a Detroit News car with a young, energetic reporter named John Bebow and we headed up there for the week.

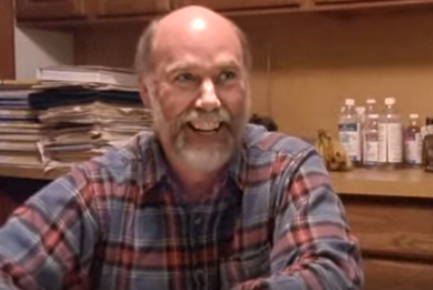

Over time, on multiple occasions, I returned to Decker to investigate the bombing for the News and chatted with James Nichols, who lived on that Decker farm where he grew organic crops.

I'm reminded of all of that with the news that Nichols died Tuesday at age 62 after a long illness. The service is Friday at the Kranz Funeral Home in Cass City.

Nichols' brother, Terry Nichols, and their buddy Tim McVeigh, who were eventually convicted of the bombing, had spent time on the farm with James Nichols. In fact, McVeigh listed the farm as his home address when he checked into the Dreamland Motel in Junction City, Kan., right before the bombing. McVeigh was eventually put to death. James' brother is serving a life sentence.

During the farmhouse raid on April 21, 1995 by the FBI and ATF, the feds arrested James Nichols on a material witness warrant and later charged him with illegally possessing unregistered explosives on his farm. He contended the explosive materials were for farm use, but was held in prison for about a month before he was released. The charge was eventually dropped, and authorities — certainly not for lack of trying — failed to find any evidence linking him to the Oklahoma City bombing.

During my visits to Nichols' farm, we would chat, sometimes in the house and other times outside. He was a nice guy, but gave off a bit of an odd vibe. He had a little bit of a sense of humor, but it was clear he didn't trust me, I assume because I was reporter.

He was chatty and insisted he never had anything to do with the bombing, or knew of anything of it in advance. I was a little skeptical, not to mention a source had shared phone records with me, which showed that Nichols called brother Terry the night before the bombing. Both shared an anti-government philosophy, one that James Nichols would share with me in conversations.

Over the many weeks, while I snooped around the Thumb area of Michigan, I would stop by the Decker Tavern, where Tim McVeigh used to drink beer. One day, a patron told me that James Nichols drove down to Oklahoma in the winter before the bombing. He didn't know why. Unfortunately, a short time later after hearing that, I went on strike at the Detroit News and never had the chance to confirm whether that was true.

In 2010, 15 years later, I was doing an anniversary piece on the bombing for AOL News and called Nichols. He didn't remember me, and after a short time, declared:

"I'm not commenting unless you've got a big checkbook." I explained that legit journalists don't pay for interviews, and that was that. But I wrote a story about him anyway, part of which said:

His lawyer says he married a few years back. Residents say he's gone on with life as usual: farming corn and beans, showing up at occasional farm auctions, stopping for a burger and fries at Kayla's Kafe, a small roadside diner just down the road from his farm.

"He's always friendly with everybody," says Kayla Nolan, owner of Kayla's Kafe. "Nobody ever talks about (the bombing). I don't think anybody thought he had anything to do with it. He's a good guy."

"It's sort of all blown over," Decker resident Phil Rockwell says. But he adds, "Nobody really knows if he had a part in it or not. Everybody has got their own opinion. I don't have any problems. A person is innocent until proven guilty."

Nichols reluctance to talk to me for AOL News may have also had something to do with his appearance in Michael Moore's film, Bowling for Columbine, which debuted in 2002.

In the film, Moore said McVeigh and the Nichols brothers made practice bombs on the farm "but the feds didn't have the goods on James, so the charges were dropped" against him.

After the film's debut, Nichols' quiet life in the country was under siege. He was deluged with "hate mail and threatening phone calls," his attorney, Stephani Godsey told me. "It was a terrible ordeal to go through."

On Oct. 27, 2003, Nichols sued for $100 million-plus,claiming defamation as a result of comments Moore made about him both in the film and on "The Oprah Winfrey Show." A federal judge dismissed the case in 2005, and Nichols lost in the appeals court.

"Michael Moore tried to portray him as the mastermind behind the bombing," Godsey said to me, adding that her client was "really upset." She says Nichols agreed to the interview because he thought Moore wanted to hear his side of the story, "but it was far from the case."

by

by