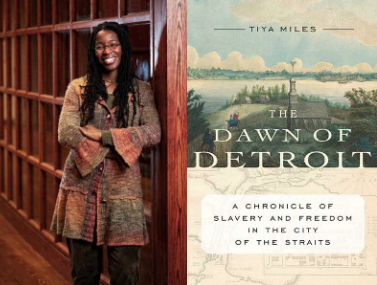

Author, U of M Professor Tiya Miles

We think of the south when it comes to slavery in the U.S., but Detroit was not exempt.

In a New York Times review of "The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits" by University of Michigan Professor Tiya Miles, Jason Sokol, a history professor at the University of New Hampshire, writes:

The events of the 20th century loom large in Detroit’s racial history: the Great Migration that pulled black Southerners to the Motor City, the rise of Motown Records, the bloody riots of 1943 and 1967. In “The Dawn of Detroit,” the historian Tiya Miles transports the reader back to the 18th century and brings to life a multiracial community that began in slavery.

If many Americans imagine slavery essentially as a system in which black men toiled on cotton plantations, Miles upends that stereotype several times over. Her book opens in the early 18th century, when the French controlled Detroit and the majority of enslaved people were both Native American and female. The town came under British rule in 1760, then shifted to American control after the Revolutionary War. Laws, boundaries and national identities were unstable; so was the institution of slavery. Miles skillfully guides the reader across this complex terrain.

Slavery in Detroit revolved around the fur trade. “Trading in the pelts of beavers and trading in the bodies of persons became contiguous endeavors in Detroit,” Miles writes, “forming an intersecting market in skins that takes on the cast of the macabre.” Some slaveholder-merchants also stole territories from Native people. Miles probes this “intertwined theft” of bodies and land.

In August 2012, Deadline Detroit co-founder Bill McGraw wrote:

Slavery in Detroit has remained an enormous secret. It is an essential chapter in Detroit's 311-year story, but it has been pushed back into archives and covered up by decades of neglect and denial. Few people, even well-informed college graduates, know that slavery played a key role in the growth of Detroit, and wealthy Detroiters owned slaves for the first 120 years of the city's existence.

When metro Detroiters talk about slavery, they talk about black men and women picking cotton in Georgia and Mississippi because that is what students in southeastern Michigan learn in school.

Yet slavery is very much homegrown. What has been called the “national sin" is also Detroit's sin. It is the origin of our racial crisis, our peculiar institution, our necessary evil. Slavery belongs to Detroit just like slavery belongs to Charleston, Monticello and New Orleans.

Many roads, schools and communities across southeast Michigan carry the names of old, prominent families that owned slaves: Macomb, Campau; Beaubien; McDougall; Abbott; Brush; Cass; Hamtramck; Gouin; Meldrum; Dequindre; Beaufait; Groesbeck; Livernois and Rivard, among many others.

Detroit's first mayor, John R. Williams, the namesake of two streets in Detroit– John R and Williams, owned slaves. The Catholic Church in Detroit was heavily involved in slavery, priests owned slaves and baptized them, and at least one slave worked on the construction of Ste. Anne’s Church around 1800. The men who funded the Free Press when it was founded in 1831 were ex-slave owners, and the paper supported slavery during the national debate before the Civil War.