Tracie McMillan dissects the Detroit Whole Foods phenomenon in Slate, examining the store's prices, customers, philosophy and effect on the city.

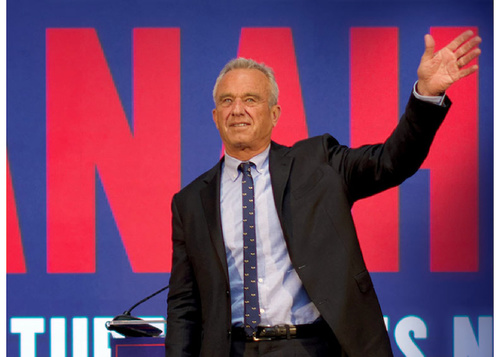

McMillan, a senior fellow at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism at Brandeis University and author of "The American Way of Eating: Undercover at Walmart, Applebee’s, Farm Fields and the Dinner Table," zeroes in on ideas advanced by Walter Robb, left, the co-CEO of Whole Foods, that healthy food should be available to people of all income levels. With the Detroit store, “we’re going after elitism. We’re going after racism,” Robb is quoted as saying.

The story was produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network (FERN)

In one part of the story, McMillan -- who had a 2012-13 Knight-Wallace Fellowship at the University of Michigan -- addresses how many Whole Foods shoppers use food stamps (SNAP):

A source who was familiar with the Detroit store and its initial sales performance, and who declined to be named for professional reasons, told me that Whole Food averages about 1 or 2 percent of sales from SNAP nationwide. If both Robb and my source are correct, 5 to 12 percent of Whole Foods’ Detroit sales are from SNAP. Since 38 percent of Detroit residents make use of the SNAP program, this estimate suggests the store isn’t reaching a cross section of the city, but a targeted, upper-income niche.

Indeed, last summer, when all the numbers had been crunched after the opening crush of business, the store found itself considering selling more expensive items, not cheaper ones. The top seller in the bakery department had been a single cupcake, baked in a half-pint jar. It sold for $6. Customers had been asking for more lamb, better cuts of meat, and higher quality wine. The busiest time at the store, Banks told me, was lunch hour, when office workers flooded the store—it is one of the few places for quick take-out within walking distance of the medical complex next door. Last November the store added a breakfast bar with $5 breakfast burritos. By autumn, bottles of wine topped out at $42, and meats at $30 per pound, instead of $20. This slide toward higher prices suggests that Whole Foods was having more success with its traditional customers than with lower-income ones.

None of this repudiates the idea that Whole Foods is a broadly positive thing for Detroit. In addition to a grocery store, the city got the gentrification signifier that it sought. Development in Midtown—and elsewhere in the city—has continued to expand, and local officials have told me Whole Foods’ success has made it easier to persuade companies to give Detroit a try. At last count, the store had created 180 jobs with wages well above the federal and state minimums. Robb has spent his own money in town, paying for new signs at the farmer’s market, persuading his suppliers to donate $150,000 in equipment to a commercial kitchen for food entrepreneurs, and hosted a benefit to raise money for the project. Even Ruff and Brown, who have little use for the store, told me they are glad it’s there.

In strictly financial terms, Whole Foods has succeeded in Detroit. Sales there have been double the initial projections, and despite Whole Foods’ reputation as a store for wealthy whites, my visits to the store suggest that its customer base reflects the fact that Detroit is majority black. When Robb was in Detroit this past September for a conference to drum up corporate interest in the city, he said the chain is looking to open a second store there.

But if you consider Robb’s broader initial goals—to reach families just trying to eat healthier, to make truly healthy food truly accessible to a broad swath of the city, to tackle the class divide in health—Whole Foods hasn’t gotten very far. Robb’s eloquent talk aside, Whole Foods isn’t too preoccupied with finding a market among shoppers like Ruff and Williams, for whom the pitch that cage-free and genetically modified are healthier than other food doesn’t merit the markup. Shoppers wanting simple, affordable healthy food, rather than an aspirational product, have better options elsewhere. And for indisputably poor people like Brown, who aspire to buy what Whole Foods sells, the prices simply aren’t low enough to work. This is not to call into question the sincerity of Robb’s desire to improve health outcomes in Detroit, but rather the impracticality—if not disingenuousness—of tying such a broad social goal to a marketing plan that requires, by definition, spending 29 percent more on your groceries.

For anyone looking to address health and diet disparities, the lesson from Whole Foods in Detroit may well be that the problem is not food, but poverty. And that is a problem that requires more than a supermarket to solve.