This repost from last May is by a Metro Detroit native imprisoned since early last week in Myanmar, where he's managing editor of Frontier Myanmar magazine. It's reshared as an example of journalism by a local writer whose plight makes international news.

By Danny Fenster

YANGON, Myanmar — At the end of a dusty road in the tiny town of Nyaungshwe stands a bamboo hut with a makeshift address, incongruous with all the other addresses along Kyak Taing Ashae Street.

It reads 313.

Upstairs, along the back wall of the Innlay Hut Indian Food House, a full-size Detroit city flag quivers on a lake breeze. The menus and walls are spattered in Old English D’s and Eminem album covers.

When Myo Min Aung, a 29-year-old ethnic Nepali from Myanmar’s famed “Valley of the Rubies,” first opened the restaurant, he struggled to stay afloat. He took and extended loans and slept at night on the dining room floor.

Then he hung a photo of Eminem — a gift from a customer — and started playing his songs, nonstop, over a small Bluetooth speaker.

Slowly, more and more people — westerners, mostly — began showing up. They wrote gushing reviews online.

“Who knew you could be so close to Detroit in Myanmar,” a review from 2018 reads. “Stan is the man.”

► Today's news: 'We are shocked and frustrated,'

posts Danny Fenster's magazine in Myanmar

Myo Min Aung rechristened himself after the eponymous superfan in Eminem's 2000 single “Stan.” He hung more memorabilia of the rapper and the city that spawned him.

Backpackers at the restaurant. (Photos: Danny Fenster)

The place is now a staple on Myanmar’s backpackers’ circuit, a must-see when visiting nearby Inle Lake.

People come for Stan as much as for the food, posing for pictures with him after eating Indian curries and posting them online. He serves dishes with braggadocio and a gangster lean, speaking in a mix of Eminem quotes and hip-hop slang.

He told me he learned English almost entirely from Eminem lyrics and, speaking to him, it isn’t hard to believe. When I messaged the restaurant’s Facebook page asking if he might be available for an interview in the coming weeks, he responded: “Yo this OG Stan, 313ShadyGangBang. If you’re at Inle Lake just drop a message. I always be at the Shady Temple.”

Myanmar, a southeast Asian nation once known as Burma, has for most of the last half century been closed to the rest of the world, isolated by dictators’ decrees and international sanctions. The gemstone-rich region from which Stan hails was even more so. The government forbade foreign visitors for fear they may steal the precious stones.

I wondered how a kid from the most secluded region of one of the world’s most secluded countries could have become so obsessed with Eminem, and the city of Detroit.

Shady’s world

It was early on a Thursday evening when I finally made it in.

The sun had just begun dipping toward the hills west of the lake, bathing the diner in its roseate blaze. It was a rare moment of quiet before the dinner rush, back when there were still dinner rushes — early enough in March that the world had begun taking notice of a new virus spreading across the globe, but too early for most to start taking it seriously.

Stan spoke about Detroit the way the devout speak of Medina or Jerusalem.

His greatest dream, he told me, is to go there and find the home of Eminem’s youth, the one pictured on the cover of the 2000 album “The Marshall Mathers LP.”

If he can’t find it, he said, he wants to get down on his knees and touch the ground, scoop up a piece of Detroit to bring back with him.

“I’d put it in jar, you know, and display it in the middle of the restaurant,” he said.

A pensive Stan recalls the journey from struggling restaurateur to tourist staple.

“People, they always say the West coast, the East coast. Man, shut the fuck up. I don’t give a fuck about the east coast, the west coast. You are in the Shady Temple, you support Detroit city goddammit! You see the D?” he said, pushing back a sleeve.

Half of his right forearm is covered in the Tigers’ Old English D, the other half in art from Eminem’s 2017 album “Revival.”

Just then a Dutch couple in their early thirties walked in.

“What’s up homie, god damn! Good to see you!” he greeted them. “Where’s your group from last night? Come on homies, sit down. God damn!”

“We’re here for the delicious food,” the Dutchman said, taking his seat. “But what about the music? Where is the music?”

“It’s coming! Easy, easy, it’s coming. God damn!” Stan said, and everyone laughed.

He poked at his phone several times and the first twinkling notes of “I Will,” from Eminem’s 2020 “Music to Be Murdered By” album came on.

The couple, paging through the menu, began nodding to the beat.

“People from so many countries come to my restaurant. I want to make Detroit famous,” Stan said. “Fuck LA, fuck New York. If I had money, Detroit is the first place I’d go.”

“Some people, they say ‘why you wanna visit Detroit, man, such a terrible place, they have the gang bang, they have the drug.’ Man, shut the fuck up, I don’t give a fuck,” he said, just as two French girls in their mid-20s walked in.

“Fuck those motherfuckers — hey ladies, welcome to Shady’s world,” he said, turning his attention toward them.

Customers gave him a faded computer printout of an Eminem portrait.

They took the table behind us. They’d read about the place online, they said, then friends from their hostel had come the night before and insisted they go.

As they paged through the menu, nodding their heads, one began singing along to “Not Afraid,” from the “Recovery” album, 2010.

More customers came in, each group following a similar pattern. They’d page through their menus and nod to the beat of some Eminem single, then set them aside and start snapping photos of the Slim Shady posters and 8 Mile Road signs.

By the time the sun had completed its descent, the tables were full. Stan turned the black lights on and the music up. More bottles of Myanmar lager were ordered.

The last thing I remember is rapping along to “Rap God,” a single from the 2013 album “Marshall Mathers LP 2,” with a German man and a Jamaican woman:

“I’m beginning to feel like a rap god, rap god / all my people from front to the back nod, back nod.”

Training days

The “Valley of the Rubies,” just north and east of Mandalay, is known for its mist-shrouded hills covered in golden pagodas, its prized Pigeon Blood rubies and its abundant heroin, which killed Stan’s father when Stan was just months old.

While other parts of Myanmar have opened significantly in the last decade, impediments remain for the valley. Tourists still must apply for a permit if they wish to visit.

Yet somehow, in the early aughts, a close friend of Stan’s smuggled in two American CDs. One was a Limp Bizkit record, and Stan had no use for it.

The other was "The Slim Shady LP."

“People ask, ‘do you understand all the lyrics?’” Stan told me. “I never went to school — I don’t know what the fuck he’s rapping about always. But when I listen — how much energy is there, man — I get much power. I feel these things, feel I am the god, man.”

When he was about 19, Stan moved to Bangkok, where he spent years as one of the more than 4 million migrant workers who leave Myanmar for higher wages and safer living conditions abroad.

With 32 percent of its population living in poverty and large swaths of the country wracked by endless armed conflict, Myanmar is the region’s largest source country for migrant workers. About 70 percent, like Stan, go to neighboring Thailand.

In the social hierarchy of migrant workers across southeast Asia, Burmese are near the bottom, forced to work the toughest jobs for the lowest wages.

This is the path Stan followed as well until, by his wit and linguistic dexterity (fluent in Burmese, Hindi and — “because Eminem,” he’s quick to point out — English), he landed a job serving at a Pakistani-owned Indian restaurant, in the heart of Bangkok’s central Silom district.

It was magnitudes better than the factories and construction sites he’d worked at. Still, the owners looked down on Burmese workers.

“They separated the people — treated the Burmese and Nepali staff this way, and the Indian and everyone else another way,” he told me.

They shorted him on tips and accused him of stealing. They fed him leftovers, and scantily at that.

“If you’re Burmese, they never feed you the chicken curry. I’d sometimes say, ‘hey man, you got a nice piece of chicken there. Can I maybe have some piece?” he said. “They’d say, ‘no! You don’t like it, don’t eat. Find another job.’”

Stan was undocumented, and he didn’t want to go back to a factory or a building site.

He was making about 8,000 Thai bhat a month — a bit over $240 — and splitting a studio with two Burmese friends for about 5,000 bhat, setting aside some money for the police.

“I’m illegal guy, I got to play the game,” he said.

So he bit his lip and apologized. He watched coworkers scoop tender pieces of breast meat into pillows of naan bread and listened to his stomach growl. He filled up on white rice.

His right forearm is covered in the Tigers’ Old English D, the other half in art from Eminem’s 2017 album “Revival.”

“You have to eat, so I ate that,” he said. “But fuck those motherfuckers, man.”

He started stealing moments to study the cooks. He saved customer receipts in four large filing boxes, poring over them to determine which dishes sold best. He memorized recipes.

“I keep everything in my brain,” he told me. “The waiters, they know everything — how to manage, how to serve the food, how to pour the wine. How spicy the tourists like the dishes. I keep watching and I keep it in my brain.”

Then one day he quit. The owners offered to nearly double his wages, to 15,000 bhat a month, but Stan was determined. He would go home and start his own successful restaurant, better than any in Bangkok.

“I knew. Like Eminem said, why be the king when you can be the god? Eminem the rap god, OG Stan gonna be the food god,” he said. “I’ll show these motherfuckers.”

Because Eminem

For returning migrants, finding legal work back home is often difficult. Many struggle without proper documentation, lost in transit or hard to renew through Myanmar’s sluggish and inept bureaucracy.

Stan’s Nepali origins made it even tougher.

His grandfather was a Gurkha – the fearless, khukuri-wielding warriors culled by the British from the mountains of Nepal, renowned for their bravery in battle. More than 200,000 fought alongside British soldiers and Burmese rebels to force Imperial Japan’s retreat in WWII, then fought alongside the rebels for Burma’s independence.

But history, geography and colonialism have conspired to make an especially toxic concoction of racial ideology in Myanmar, more punishing perhaps than America’s.

Initially granted full citizenship rights after independence, in 1947, Gurkhas were successively stripped of them after a 1962 coup d’état established a military dictatorship. By 1982, a new citizenship law stripped them even of that claim.

Citizenship — and often social standing — depend on being included in a list of 135 recognized racial categories, of which Bamar (the country’s dominant ethnic majority, which Burma is an Anglicization of) is at the top. Gurkhas are not recognized.

Stan wasn’t waiting around for permission. He borrowed about $2,000 from relatives and opened a restaurant on Nyaungshwe’s main street, taking the orders and cooking the food himself.

It did not go well.

“Everyone said my restaurant was terrible. I could hear them on the street saying ‘don’t go in there. The food takes too long, it’s no good,’” he said. “In two weeks I make 7,000 kyat,” he said — about $5. “I buy two beers and my money’s gone!”

For months he slept on a bamboo mat unfurled across the dining room floor, trying to make his borrowed money last longer. He borrowed more money.

He let his lease expire and moved from Nyaungshwe’s main street to the dusty dead end of Kyak Taing Ashae Street.

All the while, he listened to Eminem and gathered his strength, willing his destiny true.

“So I wanna make sure somewhere in this chicken scratch I scribble and doodle enough rhymes / to maybe try and help get some people through tough times,” Eminem says in “Rap God.”

One day a British woman who had just gotten over food poisoning wandered in with her husband. She told Stan it was extremely important he not use tap water – not to wash the vegetables, to steep the tea, nothing.

“They told me, ‘western stomach is different, you can’t do this,’” he said.

They were friendly and they loved the food. They returned the next day with a tablet computer and made the restaurant a page on TripAdvisor – even wrote Stan his first review.

They put the restaurant on Google Maps and showed Stan how to use Google Translate, in case customers wrote to him and he didn’t understand.

More people started showing up. A trickle at first, but growing.

He called his mother, Malar, and asked her to join him.

“I told her, ‘mom, come help me. Don’t work for nobody else. I’m gonna be famous,’” he said. “I just know this.”

With Malar in the kitchen, the service must have improved. More people were coming.

Then a Canadian couple asked if he had any music he could play while they ate, to set the mood. Of course he did.

The first song Stan played at Innlay Hut was “I Just Don’t Give A Fuck,” from the Slim Shady LP. The couple must have laughed. It’s not exactly mood music. But they also must have nodded along. Stan set the album to shuffle.

“They loved it! Their last day here they came back and dropped me this photo,” he said, pointing to a faded computer print-out of an Eminem portrait.

He started playing Eminem non-stop and took to building out the Shady Temple in earnest. He hung outside a road sign indicating a Michigan Left.

Over the following six months the trickle of tourists became a flood.

“I was happy man. People know Eminem! Local people – no one likes Eminem here. My friends all like punk,” he said.

He finally asked some customers one day how they’d heard of the place.

We read about it online, they told him. Where, he asked. They said TripAdvisor.

“I said, what the fuck is TripAdvisor?” Stan recalls.

They showed him on their cell phones. For the first time since they’d made it, Stan was staring at the Innlay Hut TripAdvisor page the British couple had made for him.

There are now more than 1,000 gushing reviews from all over the world on it, with an average rating of five out of five stars.

“I got the best restaurant experience of my life in the Innlay Hut…While pumping Dr. Dre's 808 and Eminem's lyrics, you can dig in your juicy perfect curry. But the most valuable ingredient in the Hut is the staff,” reads one from February. “I'd 313 percent come back.”

“Thanks to ‘Eminem’ and his mother. Best Indian food I've had in a long time. And that includes India travel,” reads another from March.

Stan scrolled through it all, wide-eyed.

“I said ‘holy fuck,’ man! I couldn’t believe it,” he said.

OG Stan the food god

Great songs, writes George Saunders, have meaning beyond their lyrics.

Properly executed, a song “causes the listener to assume a certain stance. Through some intersection of melody/lyrics/arrangement, it causes a shadow-being within us to get a certain expression on its face and fall into a certain posture.”

Eminem’s skin marked him from the beginning as unbelonging, a genre outsider. He comes from an underdog city that largely feels forgotten by its country, surrounded by lives and loves lost to the ravages of poverty and addiction. He raps constantly about dogged perseverance in the face of failure.

Is it possible the emotional landscapes that these things exist in are themselves infused not just in the words but in the music itself — the beats, the rhythms of speech, the tone of voice?

Like so many others, I went back to Innlay Hut the following evening. “Till I Collapse,” from “The Eminem Show” (2002) was playing. People were nodding their heads. I took the last available table.

I had a bus to catch early the next morning. Soon I would be sheltering in place in sweltering Yangon, with intermittent power outages and no lake breeze. I’d message Stan on Instagram once the country went into lockdown to see how he was doing. “Man. Fuck the Virus. Eat and sleep and watch the porn, no work. Life is suck right now,” he’d write back.

“Sometimes you just feel tired, you feel weak…you just want to give up. But you gotta search within you,” Eminem was saying, before the song’s first verse. “You gotta find that inner strength and just pull that shit out of you.”

I watched Stan move from table to table with pimp-like swagger. He was wearing a D12 T-shirt. Scrawled across the back was the phrase “Get off my Dick.”

“Thank you, OG. Come back again,” he said to a departing customer. “You the OG of this town, man. You, not me!”

The song’s hook came around:

“Til the roof comes off, till the lights go out / ‘til my legs give out, can’t shut my mouth

‘Til the smoke clears out, and my high perhaps / I’m-a rip this shit, ‘til my bones collapse”

If he can survive the economic downturn that will follow this pandemic, Stan plans on opening a second restaurant. He wants to model the building on Eminem’s childhood home, the one on the Marshall Mathers LP album cover. He’ll call it Detroit City Diner.

He’s still working through the menu, but it would include a Shady Coney, a Masala Coney and Mom’s Spaghetti – a reference to a line from the movie “8 Mile.”

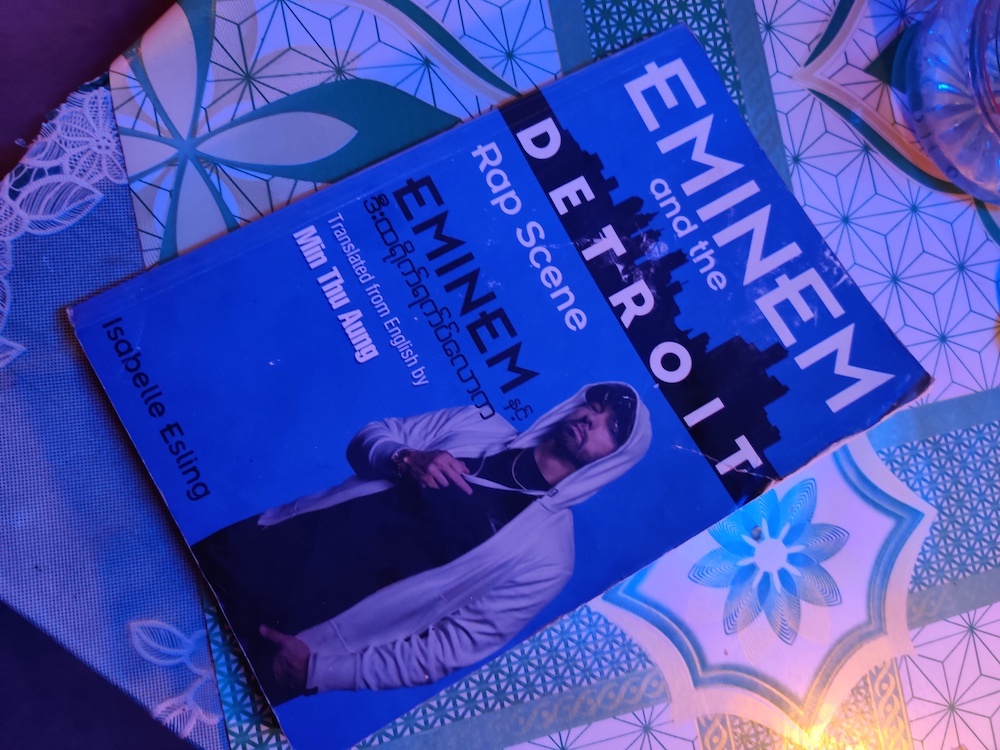

When I asked how he knew about coneys he retrieved from a desk in the corner of the restaurant a dog-eared and well-worn book, “Eminem and the Detroit Rap Scene: White Kid in a Black Music World,” by Isabelle Esling — somehow miraculously translated in its entirety into Burmese.

“Is it true, how they say in the book, there are two Detroits?” he asked me. “At a time, Detroit was really the car city, right? And they don’t do that anymore, right?”

Once he’d exhausted my knowledge of the city, the conversation turned, naturally, back to Em.

“When I put the small photo up, much more people know me. Because of him, I’m getting famous. I have much respect for this guy,” he said. “This guy, he change my life every day, man. He is the legend from Detroit city. Today I have everything from this guy.”

I asked if there was anything he wanted to say to the people of Detroit.

“I love Detroit city. I love all the Detroit people. I want to prove Detroit is the best place in the world, homie,” he said.

And, as I was leaving: “Tell everyone, OG Stan is the food god.”