In Alice Randall's telling, Detroit gleamed as "caramel Camelot" from the late 1930s to the late 1960s.

She was a child in the city during the last of those decades, a student known then as Mari-Alice Randall. Now she's a Harvard-educated novelist whose memories, research, imagination and a real-life inspiration shaped her sixth book, "Black Bottom Saints," published last month.

Alice Randall: "I don't remember not knowing Ziggy." (Photo from author)

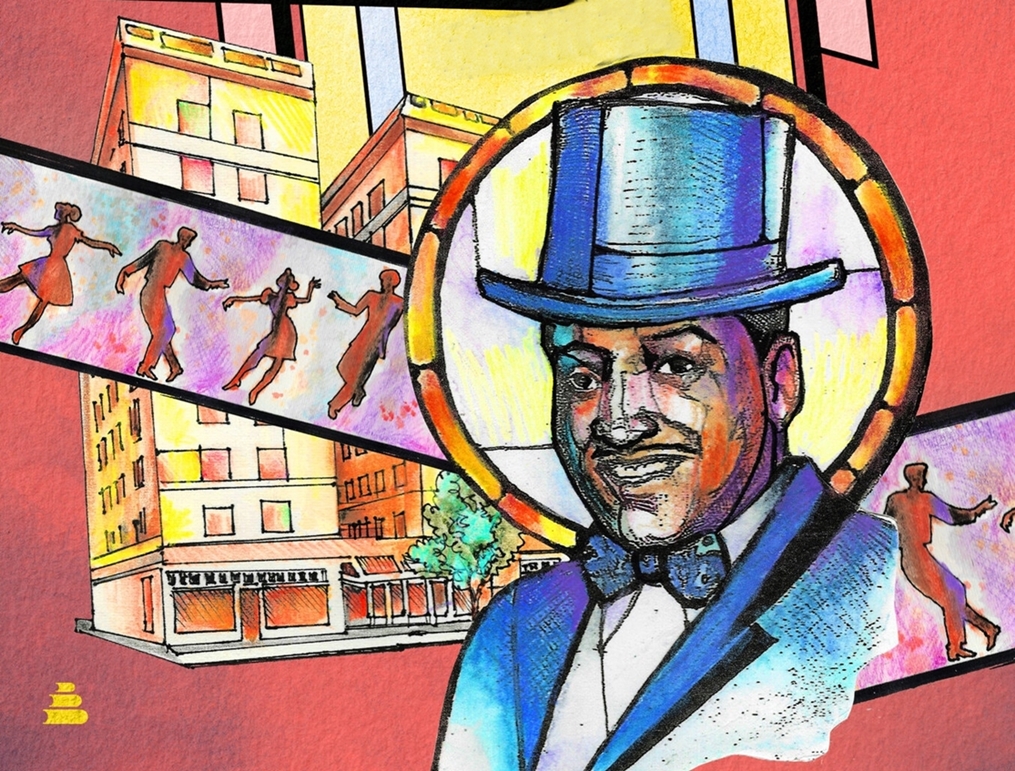

It's inspired by Michigan Chronicle entertainment columnist Joe “Ziggy” Johnson, emcee at the Flame Show Bar in Paradise Valley and then at 20 Grand Lounge until his 1968 death at age 54. The Rev. C.L. Franklin officiated at his funeral in New Bethel Baptist Church.

Randall, a writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, also relied on personal memories. From ages 3-8, she took dance lessons at an academy where Johnson aimed "to educate boys and educate girls to be dangerous citizens."

A half-century later, the 61-year-old author recalls him vividly, she tells Julie Hinds of the Free Press:

"I don't remember not knowing Ziggy. As I discovered when I was researching the book, my birth was announced in one of his columns in the Chronicle," she says during a long, fascinating phone chat about the book. "One of the most vivid impressions is he was the first writer I ever knew. ...

"I didn't know all of what he was talking about, but I loved hearing him talk about it when my father read that column aloud to me. I am a writer, and I credit Ziggy with being the person who inspired me to want to be a writer, by letting me know that writers existed."

Now that she is one, this writer weaves evocative Paradise Valley scenes through her fictionalized tribute to "our shining hours, our shining places, our shining people" in that time and place when "there was a Black Camelot, otherwise known as Detroit."

New York Times reviewer Alida Becker praises the 368-page book this month as "a rambunctious pastiche."

Ziggy is always lively and often wise. Of a beloved and overpoweringly smart English teacher he remarks, "Sometimes listening to her was like trying to drink water from a fire hydrant." A dapper friend prompts the observation that "love is the strut and hate is the stumble." ...

He reminds us that [Black Bottom] is both a place and "an attitude" — "a strong cocktail that made a person believe they could do what they wanted to do, they could be who they wanted to be."

At NPR's "Fresh Air" program this weekend, book critic Maureen Corrigan admires "a gorgeous swirl of fiction, history and motor oil."

Publishers Weekly, an industry magazine, describes the hardback as "a sprawling and intimate genre-bending chronicle of [Johnson's] adventures and tribulations."

Whether chronicling famous historical figures or local characters, Randall makes Ziggy’s saints worthy of his reflection. This works as a memorable love letter to Detroit, as well as a remarkable tableau.

Buy the book

- Pages Bookshop: $26.99 hardback, $39.99 CD ($1.50 shipping or pick up at 19560 Grand River Ave.)

- Source Bookseller: $26.99 hard, plus shipping (or pick up at 4240 Cass Ave.)

- Publisher: HarperCollins, $21.59 hard, plus shipping

- Amazon: $26.99 hard, $25.99 CD, $13.99 Kindle (plus shipping for first two)

- Barnes & Noble: $26.99 hard, $39.99 CD, $13.99 Nook (plus shipping for first two)

1951 flyer (Photo: WorthPoint Corp.)

Excerpt from Introduction chapter:

'Once there was a Black Camelot'

Nothing shines brighter than Black polished right. Too often we're too tired to get out the rag. Our brightest people and places get quickly forgotten and tarnsihed. Once there was a Black Camelot, otherwise known as Detroit. ...

And, as quickly as I am writing, evidence of our shining hours, our shining places, our shining people is getting knocked down by the wrecking ball, dynamited to pieces in the name of urban renewal, singed in the embers of righteous rebellion, buried in cemeteries, locked up in an aging memory, and coughed out into oblivion. ...

Joe "Ziggy" Johnson, 1914-1968

I preside as the unofficial Dean of the Ziggy Johnson School of the Theatre, where I teach the breadwiners' children.

That word explains Detroit to me: breadwinner. The partying factory people were those whom I first noticed when I arrived in the late thirties. Large numbers of Black men who earned a good, steady wage, doing a skilled job, then returned to the homes they owned, ready to refuel, and to dress to the nines, to head out to hear fabulous music and drink good liquor ... [at] The Driftwood Lounge, the almost-private club hidden inside the very public 20 Grand.

It wasn't just the Black factory folk in the audience, but on most nights, in most places, most people in the audience were there because of the factory folk. Black doctors, lawyers, ministers, businessmen, gamblers, dry cleaners, hairdressers, barbers, restaurateurs, teachers, policemen, firemen, bus drivers, gas station attendants, car salesmen, newspaper columnists, grocery store owners, funeral parlor directors—we all lived off the wages of factory folk.

Back in the day, because of all the breadwinners, Detroit could support all-Black hospitals, and all-Black private schools, and even exclusive all-Black beach resorts.

From Detroit Free Press, Aug. 13, 1949

The factory folk—the breadwinners—drove the Black city. Black detrroiters knew this. We have the factory folk who worked in the automobile plants their proper respect. We loved those men who did that shift work that meant eight out of ten Black families in Detroit owned the home they lived in and could afford to go out to a club to hear live music any night they chose. Our breadwinners built this city. We remember when River Rouge ran twenty-four seven. Three shifts a day at the plants meant the showbars had two shows on Sunday and late shows every night, sometimes at 2:00 a.m., for those who got off the late shift. That was the opportunity that created caramel Camelot.

All-Black audiences were fire. They brought a rare light and a heat that rated Black achievement and performance by a Black yardstick.

It was nothing unusual for a breadwinner or a breadwinner's wife to go to 52 shows a year. It was unusual but not rare to go to even 150 shows a year. Some breadwinners went to over 250 shows in a given year. The breadwinners heard so much excellent music that they became experts. And the more expert they became, the more everybody wanted to play Detroit. It was a self-perpetuating cauldron of sepia excellence.

© Amistad, 2020