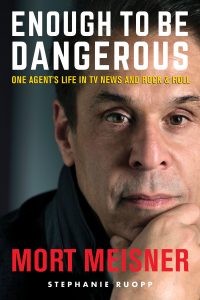

This excerpt is sponsored by Detroit native Mort Meisner for his new book, "Enough to Be Dangerous," which can be ordered before its Oct. 1 release.

In his memoir, Meisner, the TV news executive-turned talent agent shares his own stories of against-the-odds success: surviving violent abuse in his Detroit childhood home; experiencing the 1970s sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll scene as a college-age concert promoter for the likes of KISS, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, and Bob Seger; then ascending to the upper echelon of big-city newsrooms in Detroit, St. Louis, and Chicago. He exposes racism and sexism in the TV news business, as well as how he beat a cocaine addiction.

The book will also be available as an ebook from Two Sisters Writing & Publishing.

By Mort Meisner with Stephanie Ruopp

Terror was pounding my heart and ringing in my ears as I walked toward the crowd of white parents and students who stood waiting—angry, hateful, and ready for a fight—in front of my school.

I gripped my mother’s hand as we got closer. All I wanted was to enjoy the first day of second grade, and meet all the new kids who would soon arrive on buses from a nearby neighborhood.

But the angry crowd made it clear, that wouldn’t go well.

My seven-year-old mind could not comprehend their fury over plans to bus Black students whose school had burned down. To me, it was great that they could come here and attend Edgar Guest Elementary School, named for a poet who celebrated optimism about everyday life.

My naïveté was more like Mr. Guest’s philosophy, because I was excited for new kids to join our school and become my friends. In fact, my imagination had spun idyllic visions of smiling children descending the steps of big yellow buses.

Somehow, though, I feared something bad was about to happen.

So far, only one Black student attended Guest, where I’d been going since kindergarten. My classmates were kids from our neighborhood, where we were surrounded by a few other poor Jewish families and, for lack of a more accurate description, what my father called “Southern white trash.” Let’s just say it was definitely not an integrated neighborhood.

And white folks thought that was just fine during the racially tense 1950s. Now it was 1960, and the feeling remained.

Even after fire destroyed McCarroll Elementary, and the students—most of whom were Black—needed a new place to learn.

White Backlash

As a result, the school district hatched a plan to bus McCarroll’s students to Guest. Actually, it was the only option. And not a good one, according to our white neighbors.

But at the bright and hopeful age of seven, I thought it would be pretty “neat” to have a bunch of new kids at school—a whole new crop of potential friends. What could possibly go wrong?

That, plus the fact that my parents were completely on board with the idea, further cemented my faith in the viability of this plan. My dad was especially in favor of it. Not that he was a peaceful and loving person who practiced tolerance and kindness. In fact, he could be a violent and hateful man who was rarely on board with anything.

This was probably the biggest anomaly when it came to my father. Despite the vitriol and wrath that he delivered to my mother, brother, and me with startling regularity, he had no tolerance for bigotry. So he actually praised the notion of his son attending an integrated school. As off-the-hook as my dad was, he supported racial equality and the expansion of civil rights.

“Those damned white trash scissor bills have no right to have a problem with this,” he snarled in reference to our many “hillbilly” neighbors. “Those colored kids deserve an education just like you do. They can’t help it if their school burned down.”

Hindsight being what it is, it’s all too easy to predict that not all the other parents would likely share this point of view.

So, while my young imagination was envisioning a gauzy dreamscape vibrant with happy kids stepping off buses as students, parents, and teachers warmly welcomed them into our school, the reality was far from that when the buses pulled up.

“No ni**ers!” the white kids yelled. “Ni**ers go home!”

The kids threw rocks, bottles, and anything else they could find at the buses.

Their parents also screamed and threw things—proving that the proverbial apple does not fall far from the tree.

Hate electrified the air as white families screamed at the busloads of Black children.

I stood close to my mother, a safe distance from the chaos.

Glass bottles rolled and shattered on cement.

Rocks and debris flew.

The school bus doors opened.

A Black boy wearing glasses came down the steps.

He was 11 or 12 years old, and his confused, fearful expression mirrored my feelings.

A rock hit him square in the face, breaking his glasses.

Blood ran down his face; he started crying.

I burst into tears, too.

My mother rushed me across the street to the A&W restaurant at the corner of Fenkell and Meyers. She wanted to get me away from the viciousness and potential danger that was brewing. Plus, nobody was permitted into the school during the chaos.

It was 7:45 a.m., and I distinctly remember ordering a root beer and a chili dog, staring out the window and watching all hell break loose at my school.

Something in that moment changed me. It jolted something too deep within me to understand as a kid. I simply knew that I was witnessing something terribly wrong, and I wanted to someday make a positive difference for people.

Lesson In Racial Hatred

As I watched the mayhem on a morning when I should have been in a classroom, I was getting a graphic lesson on racial hatred.

The violence didn’t frighten me, because it was commonplace at home. Sadly, by that time, I had done what all kids do in an abusive household: normalize it.

But today marked my first close-up view of bigotry and racism. I didn’t understand it. And I knew on some deep and visceral level that it was wrong.

I would later learn that, at the time, Detroit had been enjoying years of prosperity and success. In fact, thanks to the fortunes generated by the booming automotive industry, the Motor City was still known as the Emerald City.

At the same time, the magic of Motown Records was electrifying the national music scene as The Supremes and The Temptations burst onto the radio airwaves and stages across America.

Yet all that wealth and wonder was worlds away from the racial inequities and tensions that had been burgeoning in poorer communities, like the one where I lived. In fact, many people in the city and suburbs were oblivious to it.

Soon, the world would know all about it. Because what I had just witnessed was a flicker of the simmering tension that would explode seven years later during the deadly 1967 riots. The insurrection would cleave a profound racial divide, cause economic collapse and a spike in crime, leave lasting devastation, and ultimately change the trajectory of a city whose crimes and conflicts I would later expose on the airwaves.