The writer, a master’s candidate in U.S. history at George Mason University and a former Detroit News reporter, lives near Washington, D.C.

By Richard Willing

Nickname aside, it's a safe bet that the outfielder Joe Jackson was wearing shoes on that day, 100 years ago this month, when he walked out of a Chicago courtroom escorted by a pair of sheriff's deputies.

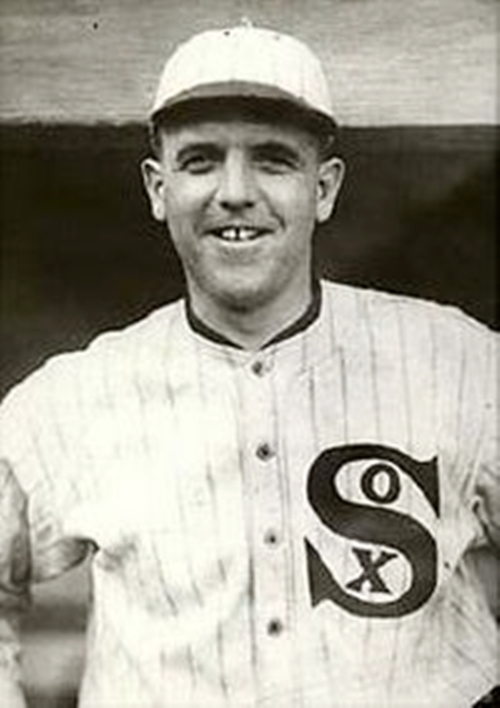

The man known as Shoeless Joe had just finished telling a grand jury that he and White Sox teammate Eddie Cicotte took big payoffs from gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series to the underdog Cincinnati Reds. Cicotte, a pitcher from the Springwells area of Southwest Detroit, testified first, voluntarily confessing after rumors of a "fix" surfaced in newspapers. Eddie Cicotte, it seems, had a guilty conscience.

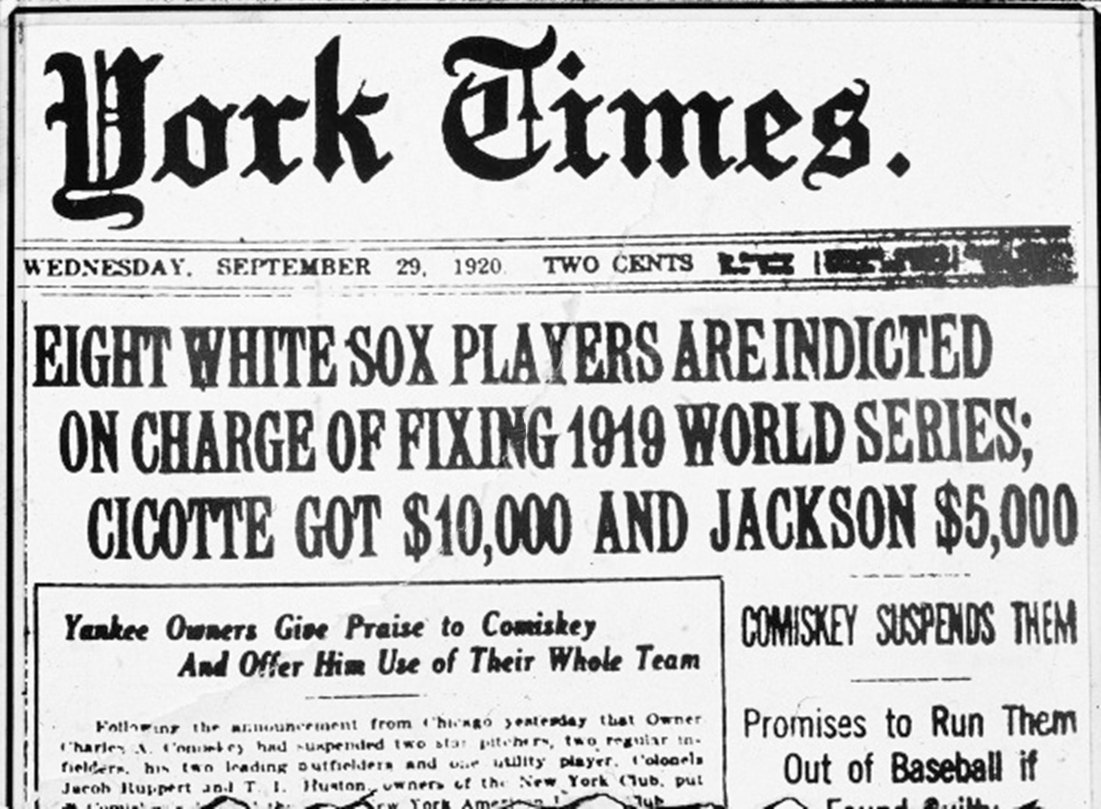

In a year that didn't lack for news – Red Scares and the Palmer raids, the beginning of Prohibition, the arrests of Sacco and Vanzetti, the tail end of a Spanish flu pandemic, an upcoming Presidential election in which women (!) would be allowed to vote – the betting scandal commandeered the headlines.

A century ago on Sept. 29.

Cicotte, Jackson and six other White Sox were charged with fraud but acquitted the next year by jurors, some of whom then joined the defendants for a celebratory dinner.

But the nation’s sense of innocence had been gravely wounded.

The New York Times called the case "an American tragedy." F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his 1925 novel "The Great Gatsby," accused the fixers of "play[ing] with the faith of fifty million people." Fixing baseball games, Chicago's Herald and Examiner opined, "might seem unimportant in comparison with disarmament, or world commerce, or the race problem, or prohibition. But at the bottom of every issue lies the national character." As Jackson descended the courthouse steps, it was reported that a youthful (and likely apocryphal) fan begged: "Say it ain't so, Joe.”

It was. The eight teammates were banned from baseball for life by a new commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

The “eight men out” were quickly dubbed the Black Sox. They live on in literature, including “The Great Gatsby” and Bernard Malamud’s "The Natural" (1952). They are central characters films such as 1989’s "Field of Dreams." In "The Godfather II" (1974), gambler Hyman Roth admits that he has "loved baseball" ever since the World Series fix.

Details still fuzzy

Even at this distance, it's hard to say for certain what did and didn't happen.

Eddie Cicotte: "I admit I did wrong."

Did the ballplayers approach the gamblers first, or was it the other way around? The players were promised $20,000 apiece – four times more than some of their salaries – but did they back out and play to win after the gamblers welched? Why ban third baseman Buck Weaver, who had heard teammates discuss throwing the Series but did not participate? And what to make of Jackson, who accepted $5,000 but then played lights out, batting .375 and hitting the Series' only home run?

On top of all this, a thick layer of quasi-history and downright mythology obscures our view. Eliot Asinof, in a 1963 offering, "Eight Men Out," led the way by characterizing the banned ballplayers as victims. This theme was amplified in the book's 1988 Hollywood adaptation.

The fix, as viewed by Asinof, was a swing of the bat aimed at Charles Comiskey, Chicago’s penny-pinching owner.

Bonus gripe

"Commie," it was argued, typically underpaid his White Sox by one-third to one-half of the going rate on other American League clubs. Eddie Cicotte of Detroit, it was said, had a special grievance -- he had been promised a whopping $10,000 bonus for winning 30 games, but was held out of games by Comiskey after he reached 29 wins that September.

But the great thing about the past, as Rutgers University historian and Yankees fan Louis Masur says, is that "it is always changing." More recently, researchers gained access to contract records archived by the Baseball Hall of Fame and concluded that the 1919 White Sox were among baseball’s best-paid teams – and that several of the crooked players in particular were exceptionally well-compensated.

(A glance at contemporary news coverage suggests that the "penniless players" theme had been shot down by prosecutors when it was introduced by defense counsel the 1921 criminal trial.)

And what of Eddie Cicotte’s bonus?

There is no record of any such promise, even though performance bonuses were written into the contracts of other players, including fellow fixer Claude “Lefty” Williams. A check of 1919 box scores showed that, rather than being benched, the right-hander was sent to the mound to clinch the pennant on Sept. 24 in what would have been his 30th win. But he got banged around by the lowly St. Louis Browns, barely a .500 ballclub, and was yanked for a pinch hitter in the seventh.

Standup frankness all along

As a reporter-turned-U.S. history-grad student, my heroes are the dogged researchers who stayed on the Black Sox case. But Eddie Cicotte is a hero, too.

The pitcher lived next to Harms Elementary School on Southwest Detroit's Central Avenue. (Photo: Google Earth)

Why? Because he was honest about his dishonesty. He did it, Cicotte told the grand jury, for a cause as powerful now as when he testified 100 years ago – the money.

He had a wife, two kids and a third on the way, not to mention his in-laws and his brother and wife, packed into a 10-year-old house (still there) on Central Avenue near Vernor in Southwest Detroit. And a $4,000 mortgage on a 5½-acre strawberry farm near Seven Mile and Merriman in Livonia Township. (The farm has long since given way to single-family homes with a current median price of about $300,000, according to Neighborhood Scout.)

Cicotte never cited those as excuses. They were just plain facts, he told the grand jury. He was sorry about what he had done, "sick all night" after deliberately losing the Series’ first game. But he never offered to give the money back. "I couldn’t very well do that," he told grand jurors.

Up-front payoff

Unlike the majority of his Black Sox teammates, Cicotte had insisted on being paid in advance.

Later, Cicotte never fought to overturn the ban, but didn't back off when the subject came up. He stayed in contact with teammates like Jackson, with whom he played unsanctioned "outlaw ball" against local semi-pros, sometimes under an assumed name. Detroit researcher Richard Bak found that Cicotte for a time worked as a sort of pitching mercenary, an arm for hire who would join teams like the Colchester, Ill., town club for a single game against an arch rival – if he was paid up front.

In 1938, Cicotte accepted an invitation from the Tigers to join 15 other former players in an Opening Day motorcade to Briggs Stadium. He worked at Ford’s in a variety of non-union jobs, including for Harry Bennett's (in)famous Service Department.

Eddie Cicotte: "I've tried to make up for it." (Historic photo colorized by Don Stokes)

He used his bribe money to fix up the strawberry farm, and sat for an interview there with Free Press sportswriting legend Joe Falls in 1965. On the subject of the World Series fix, Cicotte was forthcoming, contrite and slightly self-pitying.

'I've paid for it'

"I admit I did wrong," the then-81-year-old pitcher told the sportswriter, "but I’ve paid for it the last 45 years. … I don’t know of anyone who ever went through life without making a mistake. I've tried to make up for it by living as clean a life as I could."

We live in an age of victimization. The public stage is crowded with alleged leaders who insist that it is they who are the victims of the pandemic. Meanwhile, white protesters don black T-shirts and lay claim to the stories of racism's true victims.

Pardon me if I find Eddie Cicotte's story – all of it – to be refreshing, even 100 years later.

The old Detroiter may have laid down against the Cincinnati Reds.

After that, he was standup all the way.