Paula Yoo, a Yale graduate from the East Coast, was an intern at the Seattle Times in 1993 when she got a job offer to be a reporter at The Detroit News.

"The first question all my Asian-American friends, and especially my Asian-American journalist friends asked, was 'Are you scared to go to Detroit because of what happened to Vincent Chin?' And I have to admit, I thought about that, too."

Paula Yoo: "Meeting him [Ronald Ebens] taught me a lot about the fact that compassion and justice are not mutually exclusive."

While in college, she knew of Chin, a Chinese-American, from a documentary on his life and violent death in 1982. Chrysler plant foreman Ronald Ebens and his stepson, laid-off autoworker Michael Nitz, beat Chin after fighting at a Highland Park strip club. Witnesses alleged both blamed Chin, who they thought was Japanese, for costing U.S. autoworkers jobs. Chin was having a bachelor party at the club, Fancy Pants, and planned to marry nine days later.

"Being the adventurous type," Yoo, a Korean-American, whose parents emigrated from South Korea, ended up taking the Detroit job. And she's glad she did, having met lifelong friends and her future husband.

And while she encountered some anti-Asian bigotry, for the most part it came more from ignorance than hatred, she felt. "But it still made me mad," she said.

Yoo, who was born in Viriginia and mostly grew up in Connecticut, stayed at The News about two years before going on strike for about six months. She ended up heading west to take a job with People magazine in Los Angeles, where she lives today.

Now, Yoo, 51, an accomplished author of books for children and adults, and a screenwriter for shows like "The West Wing," has written "From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry." The book, subtitled "The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial that Galvanized the Asian American Movement," will be released April 20 by Norton Young Readers.

While researching the book, Yoo spoke with Ebens at his home for three hours. "It was one of the most profound, most intense experiences of my life as a journalist," she said.

She had been pushing to write a movie on the subject for years, but there was a dearth of interest. Then Donald Trump took office and attacks on Asian Americans escalated. In 2018, her agent agreed to take on the project as a book rather than a film.

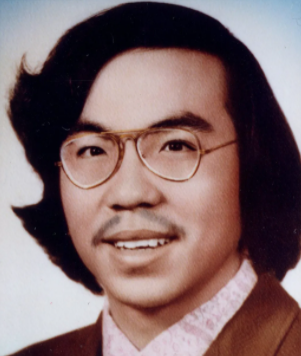

Vincent Chin

May 18, 1955 — June 23, 1982

Interest in the book grew when Trump kept calling the Covid the "Chinese Virus" and "Kung Flu,' triggering more hostility against Asians.

Last week's mass shooting in Atlanta, where six of the eight women were Asian, took interest to a new level.

"The minute Atlanta happened, my Twitter blew up, my social media. For the past two weeks, I've never, ever been this active on social media before. I was shocked. All these people wanted to interview me."

"Although I'm honored by the attention, I am heartbroken and devastated."

In the Detroit case, Ebens and his stepson bargained second-degree murder charges down to manslaughter in 1983 and were each sentenced to probation and $3,000 fines. There was community outrage, particularly among Asian Americans. The federal government stepped in and charged the men with civil rights violations.

The stepson was acquitted, but Ebens was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison. But the case was overturned in 1987 by the U.S. Appeals Court, which found a prosecution witness was allegedly improperly coached.

We talked to Yoo by phone from her Los Angeles home.

Deadline Detroit: What interested you about Vincent Chin, a story that is nearly four decades old?

Paula Yoo: It started when I was in college. His name is actually very famous for Asian Americans and especially Asian American journalists. I turn 52 this year, and so for a lot of Asian Americans my age, we were so desperate for any Asian representation in the news in history classes, pop culture, that we would just grab on to whatever we could. So that's why I've been fascinated. I remember thinking: "This is a huge story. Why don't more people know about it?"

DD: You talked about your hesitancy about coming to Detroit because of this case. How did things go here?

PY: I thought this was like, an amazing opportunity. Plus, also, I love Motown. I love Detroit, being a musician (she plays violin), I love Detroit music history. And so that was part of the big draw. I gotta go to Detroit Rock City. I went and I was very grateful because at the end of the day I met my lifelong friends and my future husband in Detroit. So I would say it was it was one of the best decisions of my life, and I'm very loyal to Detroit.

DD: You didn't get any interest in the story for years when you were planning to write a movie about it.

PY: I happened to have a random phone call from my book agent (in 2018). And I was telling her what I was working on. And she said: 'Why are you not writing a book? That's a book, that should also be a young adult, nonfiction book because you said that nobody knew about this in high school.' So I wrote a book proposal in less than a week. The words just kind of floated out of me because I have known the story for so many years. And so that's how the book happens.

I think it's for ages 12 and up. I am the first and only full-length, thoroughly detailed book about the case. There's no censoring of words. The word "motherfucker" is spelled out. I talked about the adult entertainment nightclub. I talked about the professional dancers there. I talked about the bachelor party. It's sex, drugs and rock and roll. None of this is censored in the book. It's not PG-13.

DD: Did you ever try talking to Ronald Ebens?

PY: I wrote several very polite, thoughtful letters, and left a couple voicemails for them, but they (Ebens and his wife) never answered. So, then I just drove to his house and knocked on the door, and I introduced myself, and they immediately said, "Oh, yeah, we got all your letters. We got your voicemails," and they let me in. They did say they thought my letters were very respectful. And my voicemails were respectful.

I can't reveal where he lives. I spent a few hours talking to him off the record so I can't talk about what we talked about. But we did spend three hours together, and it was one of the most profound, most intense experiences of my life as a journalist. There's a note in the book saying that some of the information and the chapters are from an informal conversation.

DD: Did he express remorse?

PY: Yeah, of course. For the record, he always said he is remorseful. He has to this day denied any racism. It's not my place to comment on what he claims. He does to this day stand by the fact that he regrets what he did. He thinks it was a moment of too much alcohol and talk. I will say that meeting him taught me a lot about the fact that compassion and justice are not mutually exclusive.

I cried in the car for about five minutes after I got out. I was just emotionally wiped out for the rest of the day. Nothing changed in terms of my point of view of the case. Do I think justice was not served? Of course I do. They pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Do I think it was unfair and unjust that they only received $3,000 fines and probation? Of course, I think that was unjust. They should have served time.

I'm not objective because I actually think it's a fallacy for people to say journalists and nonfiction authors should be objective. You can't be objective because you're a human being. The only thing we can be is fair. So I'm very fair in the book in terms of how I present both sides of the story very fairly.

DD: Did you face racism growing up?

PY: Yeah, I constantly was told you must be Chinese. And because it was always back in the '80s and '90s, being Asian American, you are either Chinese or Japanese. Back then we were told, you have to assimilate. You know, don't speak another language. Speak English. And today I realize that's wrong, because, first of all, English is not the official language of our country. And speaking Korean is just as American as speaking English.

DD: Did your parents try to comfort you growing up?

PY: I think with my parents, they were definitely of the old school. Suck it up, get around all this, study hard, get good grades, go to a good college and be successful. And, you know, success is the best revenge.

DD: And in Detroit?

PY: I had an incredibly positive and wonderful time, and I had a very diverse group of friends, and I loved that. But I will say, I stuck out because I was one of the very few Asian American woman in all of Detroit -- I lived in the city and everywhere I went, everyone I was meeting, they would say, "Oh, yeah, I saw you last week at the supermarket."

And I remember walking by one day at the Harbortown grocery store. That was right near where I lived. And a little girl and her dad, I passed them, and the little girl, five or six years old, pointed at me, and I overheard her say, "Daddy, what is she?" and her father said, "Oh, that's an Oriental." And I remember thinking to myself, oh, I know that dad means well, and he's trying to educate his daughter but you're not supposed to say Oriental, that's kind of racist. I don't think he knew that.

There were many times when I met people for the first time and they would immediately say "Konichiwa" (a Japanese greeting). I politely said hello in English and informed them I was not Japanese. They would say, "Oh my God, your English is so good, when did you learn it?" Everyone had wonderful positive, good intentions. But they didn't realize how exhausting it was for me to constantly educate people.

DD: How did you feel when Trump was always saying "Chinese Virus" or "Kung Flu" ?

PY: I was furious. I was beyond angry and in fact, when I wrote the book, the anti-Asian, racism, harassment and hate crimes had actually increased. In fact, Michigan had the highest number of hate incidents in the Midwest after the 2016 presidential elections. And that's one of the reasons the book sold, because there was already a lot of people in the media noticing.

by

by