Second of two posts on a Detroiter's book coming out Tuesday. Part 1 is here.

Here are excerpts from the prologue of "A $500 House in Detroit," which describes the author's winning bid at an October 2009 foreclosed property auction, followed by the start of Chapter 1.

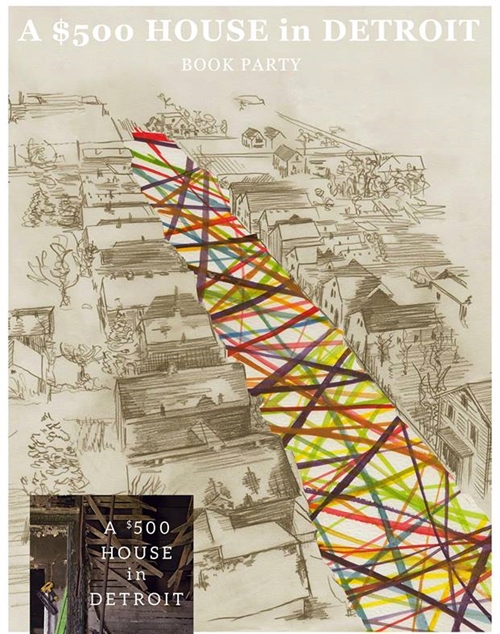

Drew Philp: "I let out a whoop." (Facebook photo)

By Drew Philp

I had come to a hotel downtown for a live auction of properties in Detroit. Starting bid was $500, less than the price of a decent television.

I looked like I'd come straight from the farm. My jeans had holes in them, my sweater was ripped, and I had on a woolen hat for the cold. I had purchased a brand new Carhartt for the coming winter and it was still stiff. There was no heat in the house on the east side where I was living.

Aside from some Greeks bidding on numerous commercial properties and some mansions in the ritzy areas, my neighbor Jake and I [then 23[ were the only white people there. . . .

The structure I wanted had run wild, open an unclaimed for at least a decade. . . .

The county was auctioning off tens of thousands of properties that day, most abandoned and in Detroit. . . . It seemed almost everyone was moving out, a city of 2 million people down to fewer than 800,000. In the 10 years between 2000 and 2010, 25 percent of the city's remaining population left . Half of the elementary-age children left.

Since the 1940s more than 90 percent of manufacturing jobs had left. No longer was the talk about "white flight," but of "middle-class flight." The city that put the world on wheels drove away in the cars they no longer made.

'Just about every cent I had'

I had three cashier's checks, each for $500, in my pocket. It was just about every cent I had in the world. I was going to attempt to buy a quaint little Queen Anne I had recently boarded up, as well as two lots next to it. If someone were to bid against me on even one of the properties, my plan would fall apart. . . .

I'd been in the stuffy room all day without lunch, and as the hours passed, My House -- what I had begun to think of as my house -- had not yet been called. I'd been running my finger over the page so often that the cheap printer ink had begun to smear. I was growing sweaty from my farm clothes and the pressure.

Just before they called the day over, the auctioneer read my page number. I slowly stood with my sign, number 3116. . . .

Then my number. I raised my sign.

"Going once."

This was it.

"Going twice."

No going back now.

"Sold! To the young man in the back."

I bought the two adjacent lots as well, and it was over that quickly. I let out a whoop and began to climb over people toward the aisle. All of a sudden other participants were wishing me luck, touching me, shaking my hand. I felt a remarkable amount of approval from the people around me in the audience, almost all black.

'Strange white kid'

Truth was, I wasn't sure how a city more than 80 percent African American would accept a strange white kid in a place whites had almost completely abandoned in the latter half of the 20th century.

"Young man! In the back. Please stay in your seat. We'll come to you. Please stay seated and a representative will be with you momentarily."

I waved my apology and within a few seconds a woman showed up with a clipboard to take my money. I signed some papers and I was a homeowner in Detroit.

Those next years as I lived in the city a massive change began, Detroit growing, shifting, molting. Old grudges clashed with new ideas and nowhere was America's fight for its soul clearer than in what was the Motor City.

Eventually Detroit would become the Lower East Side of the '80s, the Berkeley of the '60s, the Greenwich Village of the '50s. But up to that time it had only been understood as an open and active wound on the American body that we had been ignoring for decades. The greatest sea change in American culture since the 1960s was about to happen in Detroit.

Chapter 1

I moved to Detroit with no friends, no job and no money. I just came, blind. Nearly anyone I told I was moving to the city thought it was a terrible idea, that I was throwing my life away.

© 2016, Scribner

Meet the author:

Drew Philp reads and signs books Friday from 7-9 p.m. at Trinosophes coffee shop, 1464 Gratiot Ave. near Eastern Market.

Related post:

How a $500 Bid Becomes a Rehabbed Detroit Home and a Book from a Major Publisher, April 9