David Fortuck is a fugitive now. (Photo: Michigan Department of Ciorrections)

The voice on the other end was hoarse and worn, the breathing laborious, wheezing like a rusty kazoo.

David Arthur Fortuck is on the lam. The violent armed robber, given up for dead with a raging case of Covid-19, is very much alive and holed up at an undisclosed location, working under an alias, unable to believe his turn of fortune.

“I ain't going to prison, Charlie,” he said by way of burner phone. A message had been put out on the streets for him to call and Fortuck was now giving his life plan.

“I'm going to get better and then I'm going to get the fuck on,” he said. “Far, far away from here. I can't believe they let me out. It was like a birthday present or something. I mean, it was like a dream.”

Just last week, Fortuck, a habitual criminal with a long rap sheet and a single lung, was struggling for life at Harper Hospital in midtown Detroit.

He was attached to a ventilator and shackled to a gurney, guarded around the clock by sheriff's deputies.

He had contracted Covid-19 while residing at the Wayne County Jail, where he was waiting to be sentenced for armed robbery.

He was in a partial coma, given little chance of survival. But miraculously, he lived.

When he emerged from his fog, Fortuck saw that his ankles had been unshackled, his shoes returned without the laces, his trousers neatly folded, his discharge papers placed next to those.

“I said to myself, 'This has to be some kind of trick, some kind of setup,' you know?” Fortuck said. “I mean, the guards just vanished, disappeared, man. I was supposed to be going to the penitentiary. I thought I was dreaming.”

Fortuck lingered in bed a few more days, gaining strength while he “cased the joint” for deputies. But there were none. They were long gone. It was three days past his 53rd birthday when he decided to accept the get-out-of-jail-free card and make a run for it.

“I looked out the window and there was nobody there, so I disconnected from the machine and left. I'm not a stupid man.”

He was advised by hospital staff that he was too weak and sick to leave. But seeing how there were no cuffs or cops to compel him to stay, Fortuck slipped on his laceless shoes and the one-lunged, bipolar ball of Covid hit the streets.

“Did you know the city buses are free, Charlie?” he coughed, choking back the wonderment of it.

“I availed myself of them. You enter in the back now. I tried to practice the appropriate social distancing. I mean, I'm not an animal.”

And with that, Fortuck made a beeline for the suburbs.

“I mean, the treatment is better out there for one,” he said. “Besides, it's like a when a nuclear bomb goes off? You try to run away from ground zero, you know? Get away from the radiation. Detroit and the jail is ground zero.”

He was reminded that he was indeed that smoking ball of radioactivity.

"True,” he said.

Better if he'd die elsewhere

So how did “Hard Luck” Fortuck get kicked from custody and back into civil society? A habitual violent felon facing a 5-year sentence while residing in the Wayne County Jail?

He was released on what is known as an administrative jail release, whereby the sheriff has sole authority, by virtue of the courts, and sole discretion to let inmates back on the streets due to housing emergencies. And there is no bigger emergency right now within the rotted county jails than the Covid cluster raging inside.

In fact, Sheriff Benny Napoleon has seen fit to release more than 600 people over the past month. None have been tested for the virus before being put back on the street.

“He was released via AJR, April 21st,” the sheriff's department acknowledged in a brief statement. “He was a medical risk and was at the hospital at the time of release.”

That is all well and good, but the sheriff released a violent inmate who was headed for prison. Furthermore, it is hard to see how this was a medical risk when he was shackled to a hospital bed. Further still, the paperwork said he paid a bond of $1,250 – which he did not. Further still, he was released without an electronic tracking tether.

Why was he let go?

There are three theories among deputies and Fortuck himself.

-

The sheriff did not want to pay for round-the-clock guards.

-

The sheriff did not want to pick up the hospital tab. If Fortuck died a free man, then the medical bill would be buried with him.

-

The sheriff wished to avoid the death statistic, which would only bring more scrutiny on his jailhouses.

The troubles there are well-chronicled: Nearly 200 jail employees have tested positive for coronavirus. More than 200 have been quarantined. The two top doctors died from the virus, the sheriff unaware that one had been dead a week. The commander of the maximum security facility and a ranking corporal are also dead. One inmate who was released on AJR earlier this month, took the wrong bus and then a taxi across the county before dying at home. The public was told none of this.

Despite months of warnings about the state of the fetid jails, politicians are silent. Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, who oversaw the collapse of the jailhouses when he was deputy county executive, is silent. Warren Evans, the Wayne County executive who was once the sheriff, is silent. The current sheriff, Benny Napoleon, who was once an assistant county executive, is silent. Governor Gretchen Whitmer, who is off doing comedy shows, has been mum. State Attorney General Dana Nessel, to her credit, did get some dental masks donated for the inmates at the jails, and issued a press release about it.

Meanwhile, Hard Luck Fortuck, the one-lung, bipolar time bomb, was roaming the streets.

A nervous friend arms herself

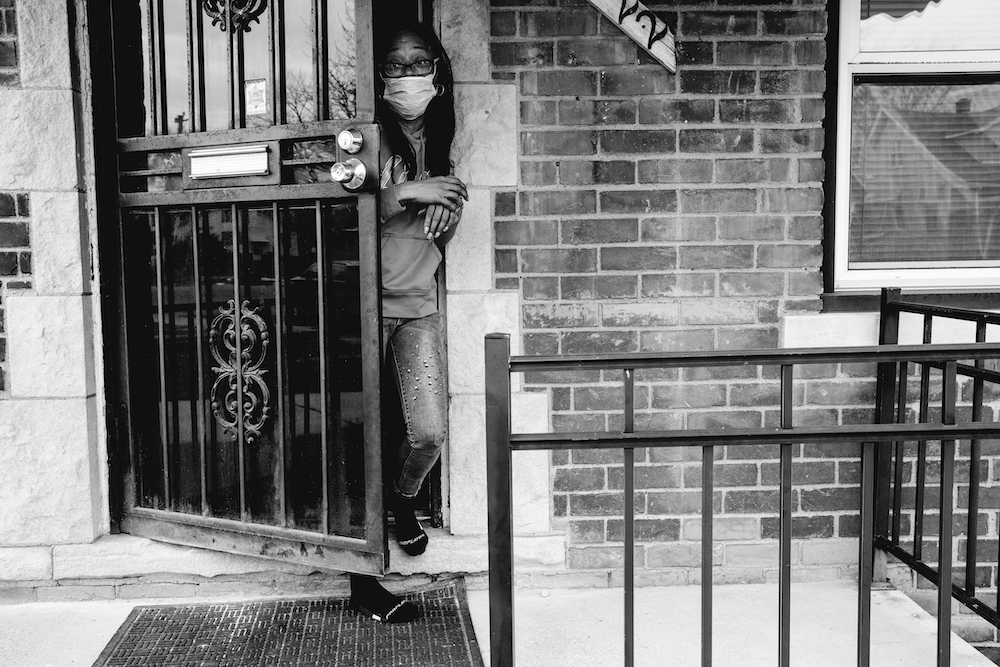

Trevious Lane-French at home, worried about a knock on the door (Photo by Blaze Foley)

“They just unleashed him out here among us,” said Trevious Lane-French, an old friend, who resides at Fortuck's last known address. “I mean he's infected with Covid, for one. He's also bipolar, he gets violent when he's without meds. It's a real potential for disaster.”

After Fortuck called her from the hospital to inform her of his good luck, Lane-French felt compelled to make a trip to the Double Action gun shop in Madison Heights. She purchased a 9mm pistol in case Fortuck came knocking.

And he did.

There was no episode, however. No scene. No violence. She gave him some money and he went away.

“She's right about me,” Fortuck said. “I don't feel I belong in prison, I belong in a mental institution. When I left the hospital, I wasn't given any medication.”

Flush with some cash, Fortuck made his way to the suburbs. He patronized a Metro PCS store and bought himself a burner phone with prepaid minutes. No telling how many people he may have infected at the store.

Next he went to the Mobil gas station, where he pawed through the sandwich cooler. Egg salad. Turkey salad. Ham and cheese. Eventually he settled on the turkey and Swiss.

“I'm a little bit of a foodie,” Fortuck said with some real dignity. “It was white bread, I believe. I paid for it.”

No telling how many people – or sandwiches – he may have infected there.

Fortuck booked a motel room, spent the night, watched the governor on a morning show. He checked out and warned no one of his soiled sheets.

“No, I didn't tell anyone I have Covid,” he said, regretting in retrospect that he did not tell the maid. “I didn't think about that one. I'm just trying to live, you know? Every human being's motivation is survival when you get right down to it.”

David Arthur Fortuck is not dead. His sole lung is still very much working. And he is not legally a fugitive.

But he knows the law will come hunting once his story hits the news. He knows they'll be angry, and embarrassed.

“Honestly, they really fucked up here,” he said from his undisclosed location, off the streets now, his prepaid minutes running low. “But I'm going to get better and make a run for it. Wouldn't you?”

by

by