"Defund police" has become a rallying cry in Detroit and across the country. The two words reflect a strategy that's far more complicated. (Photo: Michael Lucido)

In the early morning hours of Sept. 14, 2018, a Detroit SWAT unit descended on a west-side home, acting on a lead a homicide suspect was inside. Officers in helmets and protective vests rammed down the door, according to a lawyer who reviewed the case, and encountered a Black man holding a gun. Within moments, he was shot dead.

The man, 46-year-old Detric Driver, was not the suspect, and no one inside the home was involved in the homicide. Driver, who based on the lawyer’s interviews with witnesses may have thought there was a break-in, simply made the grave mistake of grabbing a gun.

The case, which did not result in charges against the officers involved, bears strikingly similarities to the March police killing of 26-year-old Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, which has sparked a nationwide uproar and calls for justice. An overnight raid in which witnesses say officers failed to knock, bad intelligence that led them to a home with no suspects or evidence, and a Black person killed for their distant affiliation to someone believed to have committed a crime. (Driver’s niece was the homicide victim’s half-sister.)

A growing movement to reimagine public safety in the wake of a spate of high-profile police killings sees the incidents not as flaws, but rather features of a broken system that disproportionately ensnares people of color and has a propensity toward violent confrontations.

► Related: Demonstrator Says She Suffered Skull-Splitting Brain Injury from Detroit Police Rubber Bullet, June 7

► Video Shows Officer Hit Restrained Demonstrator with Baton — Detroit Police Say it Doesn't, Aug. 24

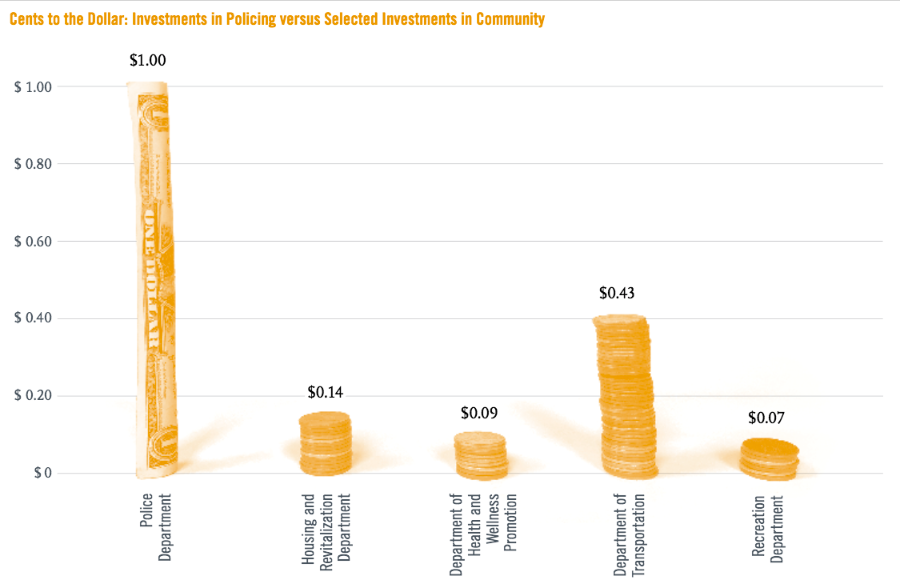

Police officers — armed and trained to treat each encounter as a potential threat — are America’s first responders, dispatched to deal with everything from murders to homeless people in an inconvenient location. And cities spend huge sums to uphold this norm: In cash-strapped Detroit, police expenditures last year were $316 million, comprising about a third of the general fund.

Tristan Taylor, left. (Photo: Nancy Derringer)

And so, protesters who for weeks have gathered nightly nationwide and in downtown Detroit seek more than reform. They’ve rallied around the concept of “defunding” — or, more accurately, divesting from — police and reinvesting in social programs to produce better outcomes. In the reality they envision, some police duties would be offloaded to social workers, mental health professionals and de-escalators.

“No matter if it’s a so-called good cop or so-called bad cop, the system of policing is steeped in racism and hurts Black communities,” says Rod Adams of the grass roots group Detroit Action, noting some scholars have traced its origins to slavery. “It’s time to divest from something that hurts Black people and …. invest in their futures. There’s (places) all over the country that basically operate in a world without police, and those are suburbs, because there are fully-funded schools and (people have access to) well-paying jobs.”

Perhaps more than anywhere else in the U.S., the idea hangs between extremes. Detroit is the nation’s Blackest, poorest big city, with limited funds to meet the needs of residents. But Detroit is also the nation’s most violent crime-ridden big city, where a historically low number of police officers work for comparatively low pay.

Given the complicated landscape, many Detroit activists have broken from their counterparts across the country and stopped short of calling for full defundment and the abolition of police.

The Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality has said it’s not anti-police, describing the often slow response of Detroit’s spread-thin force as itself a form of brutality. Tristan Taylor, who’s led nightly downtown demonstrations in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, told Deadline Detroit the notion of police abolition has “caused some concern” in that it could open the door for private forces with no oversight to replace city officers. And Detroit Action ultimately sees a city without armed officers as an end goal should crime drop in concert with increased community investment.

Increased spending

Though the “defund” movement contends crime can be eradicated in the long term by reinvesting police resources in social services and educational programs, Mayor Mike Duggan, a former prosecutor, has said he does not “see the two conversations as being linked.” For him, crime is a present-day problem that requires an immediate and conventional response.

“I don’t think there’s a community meeting I’ve been in where the community did not ask for more police,” he said at an early June news conference. “My responsibility as the mayor is to meet the needs of this community, not by cutting another essential service.”

(Source: Freedom to Thrive via City of Detroit budget, FY 2017 - FY 2020)

Increasing law enforcement spending has been a top priority for the two-term mayor since he took office in 2014, following pre-bankruptcy cuts to the department. Police spending has grown by $52 million, or 17 percent, since 2015, and officials say overall crime has seen double digit declines, in line with major cities around the country. Violent crime, however, dropped by only 1 percent between 2014 and 2018, according to FBI data.

The department’s budget will largely remain untouched as the city trims elsewhere to bridge a projected $348 million shortfall caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Cut instead will be services like the demolition of abandoned houses, previously another top priority for Duggan, who’s described Detroit’s estimated 20,000 vacant structures as crime magnets.

Much of the increased law enforcement spending has gone toward boosting starting officer salaries, which were cut to about $29,000 and today stand at about $41,000. Still, officers remain “grossly underpaid” when compared with their counterparts in the suburbs and mid-sized cities around the country, a 2018 report by Detroit’s Legislative Policy Division found. Getting them up to the average for officers in the departments reviewed would likely require at least $21 million in additional spending each year, the report said.

Police Chief James Craig, meanwhile, has said he wants to boost starting pay to $60,000 and add 1,000 officers over the department’s approximately 2,500 total sworn.

The poor pay has fueled an ongoing retention problem that the police union and others warn puts the public in greater danger. Half of the department has under five years on the job, according to the officers’ union. And officers risk fatigue as they clock more overtime to account for a stubborn personnel gap. Overtime spending accounted for 13 percent of the police budget in 2017.

The vetting process for new recruits has also been expedited amid a mayoral mandate to boost ranks. John Bennett, a former department recruiter who retired four years ago, said he usually spent four or five months working a candidate’s file, checking their background and meeting with them face-to-face, a similar timeline to that of the Ann Arbor Police Department. Now, he says his ex-colleagues can push someone through to the academy in as little as four weeks.

“It’s dangerous,” said Bennett. “When you're processing people at that pace, you're gonna get people who should not be on the job in the uniform.”

(The department said the process has been expedited because it now can “check people electronically.”)

Proposed cuts

But divestment advocates seek an end to a number of expenditures beyond cutting officer pay. They include:

-

Criminalization of the poor. About 1 in every 7 people booked into the Wayne County Jail, whose own budget is more than $100 million per year, are there for charges related to suspended licenses, registrations, and lack of vehicle insurance, according to a report by the Vera Institute. Another 9 percent of jail bookings are reportedly for failure to make child support payments.

-

Replacing officers with social workers or other professionals for complaints where there’s a low risk of danger. City records show Detroit police respond to thousands of such calls. Between 2016 and 2018, for example, they were dispatched for 2,400 reports of lost property, 1,000 calls for assistance for senior citizens, 400 vehicle fires and 400 noise complaints. In the past several months they’ve stopped more than 1,000 people for social distancing violations.

-

The Project Green Light surveillance program, whose cost is primarily shouldered by businesses but has seen $12 million in city investment since its 2016 inception, with another $9 million in state transportation grants for roadside cameras. Preliminary research by Michigan State University has found no evidence the cameras drive down violent crime. Project Green Light has, however, helped Detroit police solve crimes after they occur, including 40 in 2018, according to a department memo obtained by Deadline Detroit.

-

Facial recognition technology, which has cost the city $1 million and whose contract is currently up for renewal through 2022 for about $220,000. Opponents have argued it should not be used because it has a tendency to misidentify Black people (a lawsuit alleging the first misidentification was filed Wednesday), but police have said a technician reviews results before a face is considered a match.

Councilmember Mary Sheffield’s office has asked for a detailed accounting of all police expenditures and is currently examining dispatch data to see what calls police may “not be best-suited” to respond to. She says she plans to use her findings during an upcoming debate over budget amendments.

“Police are in some ways necessary, but we do need to re-evaluate how the police interact with our communities, particularly communities of color,” said Sheffield. “And we need to reevaluate the way we allocate funds and figure out what areas we can disinvest in and reinvest in things that are more preventative and less reactionary.”

Officials in other cities have heeded calls for divestment. In New York, a city council proposal seeks to trim $1 billion from the police department’s $6-billion budget. Los Angeles’ mayor has proposed trimming up to $150 million from that force’s budget. And Minneapolis officials have pledged to disband their police department, saying it could not be reformed, though it's not yet clear what will take its place.

In Eugene, Oregon, social workers already respond to 20 percent of 911 calls, resulting in an estimated savings of $15 million per year.

‘A knee away’

Amid nationwide backlash against police, Craig has described Detroit as immune — a city that enjoys a positive relationship between its force and citizens. He credits years of federal oversight that reduced excessive use of force and illegal detentions by the department, as well as a pivot to community policing.

"I don't understand why some cities are just now figuring out changes need to be made, but some police agencies have done it right," Craig was quoted in a Detroit News story on departmental reforms. "Detroit's one of those agencies."

But though the department has made strides in the last two decades, it is not less problem-plagued than other forces.

The city paid out $19 million in police misconduct settlements between 2015 and mid-2018, and 64 officers were criminally charged between 2016 and 2018 for incidents on and off the job, according to reports by WXYZ. Only Baltimore fared worse among major cities that track all criminal conduct by officers, with 76 officers criminally charged, the station reported.

Officer Jerold Blanding. (Photo: Instagram, FatalForce)

Meanwhile, the department has killed nine people since 2015, a death toll in line with that of the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, a city with a third more officers and roughly the same number of residents.

At least two killings in addition to Driver’s raised questions about why the victims were pursued in the first place. Jerry Bradford Jr., 19, and Raynard Burton, 19, who were both unarmed, were killed in separate incidents in 2017 that began when they sped away from officers.

Bradford died when he crashed his car as police chased him through a residential neighborhood, in violation of department policy. The officers, 26 and 28 years old, were later charged with willful neglect of duty for failing to report the chase. They were each sentenced to a year probation and kept on the force.

Burton was shot earlier that year when Officer Jerold Blanding said the teen reached for his gun following a foot chase with no witnesses or camera footage. Only later did police learn he’d been involved in a carjacking.

Blanding, a department veteran whose Instagram handle at the time was “FatalForce” and who had been the subject of two prior excessive-use-of-force lawsuits, was not charged. He was charged the following year for a separate, off-duty incident in which he showed up at a crash scene apparently drunk and carrying three guns, even though he’d been barred from carrying a weapon for the department. He retired shortly thereafter and receives a taxpayer-funded pension.

“We're really not any different than Minneapolis, we’re just lucky,” said Bennett, the former Detroit police officer. “Having ... seen the inside of what they’re bringing into the agency, I think we're honestly just a knee away from a similar situation.”

But Bennett does not see replacing officers with unarmed public servants as a solution, saying “any situation can turn dangerous.” Instead, he believes pay should be boosted to attract higher quality candidates who may have backgrounds in social work or mental health. He also says African-American hiring should be emphasized, pointing to a string of racist episodes involving officers in recent years, including the mocking of a young black woman on Snapchat.

Since the elimination of residency requirements, a quarter of the force lives in Detroit. And it looks less like the people it serves, with just 55-percent Black officers in an 80 percent Black city.

Improved relations

At the neighborhood level, many residents see police as allies in making their streets more livable.

In Pingree Park, a mixed-income east side neighborhood abutting the more affluent Villages, community development coordinator Edythe Ford says police are a necessity, but that increasing access to opportunity for Detroiters would have the greatest impact on crime.

“We don’t have that adversarial type relationship with the police,” said Ford, 61. “We don’t have the abusive force we used to before (federal oversight).”

Ford and Mac Farr, director of the Pingree Park Association, say they got a first-hand glimpse at what fewer police would mean for Pingree when hundreds of officers were sidelined by the coronavirus outbreak this spring, and the community was suddenly overrun with drag racing and gunfire.

“At the end of the day, can a social worker really address drag racing? You need to have some power behind addressing some of these issues our communities are facing,” Farr said, adding that police work could “be complemented by softer services.”

“If you’re at Shoemaker and Bewick (streets), in some cases you need the police,” he said. “(‘Defund police’) is coming from such a position of extreme privilege that I think, OK that’s cute, you can take that language and go back to the West Village and rest easy.”

‘Structurally evil’

For Jermaine Carey, a longtime friend of Driver’s, the latest round of police killings across the country has reopened a wound.

Carey had known Driver since he was a teen, and saw him as a big brother.

Detric Driver. (Photo: Jermaine Carey)

The 46-year-old was newly married when he was killed by police in September of 2018. He was said to be a “working man” who had at various points been a carpenter, window washer, and just obtained his trucking license.

He was also a fixture in the Muslim community on the west side of Detroit. After his death, Carey says he managed to raise about $30,000 in donations for Driver's family.

“He never was misguided,” he said. “He had a glow about him. As we say, he was a ‘friend of Allah.’”

Carey has never made sense of Driver’s killing. Police initially said they zeroed in on Driver's house because his brother’s car was there, and it had been seen at the house where the murder took place. Driver, they said, was lying on a couch and pulled an assault rifle. Details of the Michigan State Police investigation into the use of force, which was said to include body camera footage, have never been released.

Carey was dismayed by Craig’s statements following the shooting, in which he ticked off Driver’s criminal history: a CCW and fraud charge. Driver was also a former security guard at Masjid Al-Haqq, a mosque whose imam was killed by FBI agents a decade prior, in a case that prompted a civil rights lawsuit that was reportedly tossed on a technicality.

“Everyone who knows his character knows he didn’t deserve to die the way he died,” said Carey. “The city did him so bad, even in death. Craig tried to frame him as a hooligan, but this is poverty, this the hood,” he said, referencing the previous charges.

For Carey, a resident of the Warrendale neighborhood, on the west side, reforms are not enough. He doesn’t believe changing the department’s racial makeup will do good when it was a majority-Black force that killed his Black friend. And body cameras, utilized by the DPD after the last nationwide call for reform five years ago, did little.

“How can you reform something that’s structurally evil, that’s rooted in evil? What can you change about that to make it positive? Every time they add something, they find a way to manipulate it, so we gotta abolish it, we gotta restart.

“Of course nobody wants to live in a lawless land, but there’s lawlessness within the system.”

Top 10 articles countdown

10. Eminem-obsessed restaurateur gives Myanmar tourists a taste of Detroit

9. Hakim Littleton was killed for shooting at police. Detroit was his undoing

8. Who is Tay Crispyy? ‘Mr. Reporting Live’ claims a place in Detroit media landscape

7. Gallery: Detroit landmarks and roads and the slave owners they’re named for

by

by